Now there was a man of the Pharisees named Nicodemus, a member of the Jewish ruling council. He came to Jesus at night and said, "Rabbi, we know you are a teacher who has come from God. For no one could perform the miraculous signs you are doing if God were not with him."We are a storytelling people and many of the stories we tell are tales of origin. We are interested in our past--which means not just what we've experienced, but what those before us experienced. We tell these tales of personal and corporate past so we can better understand our current selves, an understanding based in weaving together the tales of the past with stories of future possibilities. Is it any wonder we are obsessed with knowing where people are from or where they are going? The tales of past are the roots of our identification--who we are--while the stories of possibility are how we want to identify ourselves and others.

In reply Jesus declared, "I tell you the truth, no one can see the kingdom of God unless he is born again."

"How can a man be born when he is old?" Nicodemus asked. "Surely he cannot enter a second time into his mother's womb to be born!"

Jesus answered, "I tell you the truth, no one can enter the kingdom of God unless he is born of water and the Spirit. Flesh gives birth to flesh, but the Spirit gives birth to spirit. You should not be surprised at my saying, 'You must be born again.' The wind blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound, but you cannot tell where it comes from or where it is going. So it is with everyone born of the Spirit." John 3:1-8

Let's talk about our corporate religious origins, so we can better understand our place today, and where we want to go from here.

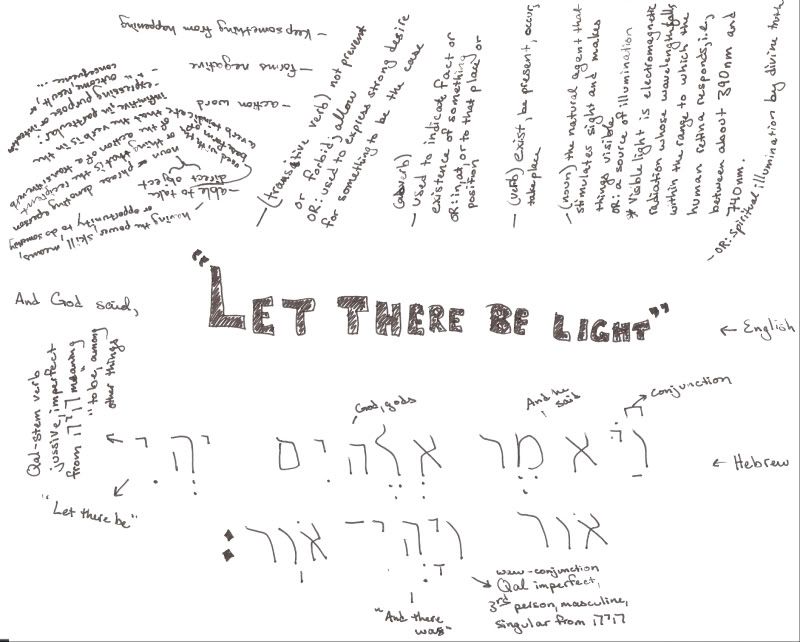

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. And God said, "Let there be light," and there was light. God saw that the light was good, and He separated the light from the darkness. God called the light "day," and the darkness he called "night." And there was evening, and there was morning—the first day. Genesis 1:1-5Let me be honest with you. I have a hard time conceiving of "the beginning." I can handle thinking about God being involved in starting what we know as existence. But what happened before then? Who created God? Who created what created God? Who created what created that which created God? I would ask more questions if I were grammatically advanced enough to construct more sentences like that.

I was watching Escape from the Planet of the Apes recently and I heard a story I find very apropos. A man shows a painting of a landscape.

and a fourth picture ...

and so on going to infinity.

When I think about the beginning in Genesis, I think about this infinite regression, about God having to constantly paint pictures in which God is painting the picture. And if God is always re-painting, has God ever been not painting? Is God still painting?

Somebody once asked St. Augustine a similar question: "What was God doing before God created time?" Augustine deigned God was preparing hells for people who ask such silly questions. Funny answer, but not helpful. God must have been doing something before "the beginning" in question. God must have been creating things other than the heavens and earth--you know, preparing things for future creations. Like, before God could speak something into creation, God had to create language and give language the ability to create things. And after creating language, God have to give words meanings.

In effect, before God could say:

God had to say, "let the word "let" mean "to allow." Of course, God wouldn't be speaking English and maybe not even Hebrew. Regardless, even before that sentence, God had to step back and would need to define every word used in that definition. And before that ...

well, you get the point: infinite regression, Planet of the Apes, a beginning before the beginning. We keep having to step back and see another picture of God drawing the picture.

In trying to figure out where something like language actually began, you'll turn up about as much as you will trying to delineate North Carolina geography. At our East, we have the flat coast. Further towards the middle, we find the piedmont, and the mountains are in the west. The mountains are distinct from our coast, but you couldn't draw a line where one started and the other ended.

Likewise language doesn't exactly have a beginning; it was not created--whatever that implies. And beginninglessness makes it difficult for us to understand our past and our origins, because we're used to everything having a beginning.

And if language doesn't have a beginning and God used language to create, then we don't have a beginning either, which makes sense in its nonsensicalness. Let me explain.

I was born, but birth wasn't my beginning. Before birth, I developed in the womb. Before development I was conceived. Before conception in the body, I was conceived of in my mother's mind, who told me she always wanted two kids (me being her second). And before she could even conceive of me, all kinds of environmental, psychological, and relational influences interacted with the woman who is now my mother, just like it did with my father. And they had to be born and conceived, too. I am not just a product of my time and my parents and their time; I am also a product of my parents' parents and their time, and so on and so forth (or, so back) until we reach the origins of humanity and then the origins of the earth and then we're talking about the beginning and language and the beginning before the beginning. So, although each of us was born, we have no starting point other than God--our Alpha and Omega (Rev. 21:6).

The Blessing of Babel

To better understand the significance of beginninglessness for our present, let's look at the story of language's development according to Genesis.

Even without a proper starting point, the story continues today--it has a past, present, and future. As the story goes, Yahweh once saw a bunch of people all speaking one language. They were building a tower in order to make a name for themselves. They wanted to be unified, and God said they could do anything, since they all spoke the same language.

I can't help but wonder if Yahweh was a little sarcastic when expressing worry about those people and their tower. Could they really do anything just because they could speak the same language? I've never known language to be perfect. I speak the same language as a lot of people, but I still misunderstand them often. Any of you in any sort of relationship know exactly what I'm talking about, how one word or sentence can mean something completely different to the person who hears you. Even before language had been officially "confused," it was still confusing.

On the one hand, we definitely communicate more effectively with people who speak the same language we do. On the other hand, I still hear a hint of sarcasm when Yahweh talks about descending to the people, or rather, condescending to them.

In Genesis 11:7, God says, "come, let us go down, and confuse their

language, so they will not understand one another's speech." And after that condescension, Yahweh makes language something new: "Let people use different words to mean the same thing and similar words to mean different things," which is basically how language worked anyways, but Yahweh magnified the confusion by creating "new" languages.

If you've been listening, you'll notice I just said Yahweh created languages, even though, earlier, I said language could not be created. I could distinguish between a language and language in general, which would be a fine distinction. But here's what really matters: God took what the people were speaking--(uncreated) language--and made it new, in effect, the story says God created or "recreated" language at Babel.

And this whole "new language thing,"not such a bad idea, actually. Yahweh blessed humanity at Babel. Just think of all the positive consequences of heaven condescending to the tower: new literature, poetry and philosophy; the beauty and wonder of translation; and a new pursuit of community amidst differences.

But even with all these new blessings, I bet it was easy to scorn the blessing of Babel. I can imagine it would be easy for these post-Babel persons to think about how nice it was in the good ol' days when everyone spoke the same language, even though we know they weren't always understood. New things come with pros and cons. It's often easiest to think of the pros when you're reflecting on the past and the cons when you're in the middle of experiencing.

As with language's beginninglessness, so with us. When we are reborn, we face wonderful grace and new troubles. Amidst the new troubles, it is hard not to look back and think how nice it used to be, despite the current grace.

No Turning Back

With some understanding of beginninglessness and rebirth, let me tell another story from our religious past so we can think more about handling the newness of rebirth, cutting the metaphorical umbilical cord.

As the story goes, Lot is told to take his family and flee from a horrible place before it is destroyed. Just so happens that horrible place was their home, Sodom. Horrible or not, it was their home. How can you just up and flee your home? They didn't have time to pack, get a U-haul, and say goodbye to people; they didn't move, they fled. Sure, most of the people in town just did some pretty horrible things, but I'm sure there were other things to make the sweetness of leaving a little bitter. You know, the dog loved the backyard; there was a pretty good library; Lot's job paid pretty well and had nice benefits.

But Lot and his family were asked to leave immediately without looking back. To leave their home and all their possessions. To start afresh somewhere new, with no real direction, just a command to flee and start over, somehow. A fresh start. A rebirth.

Lot's wife looked back and then became a pillar of salt.

Lot pled to remain near his home, so he wouldn't have to go too far away. His request was granted and he settled his remaining, non-mineral family members in a nearby, small town.

We can't completely relate to Lot's story. We've never been in his or his family's shoes, thank God. But, I've had a very literal call to leave home and start new somewhere else. I've had that one a few times, actually, and I am already interacting with that call concerning the next few years of my life. When negotiating that first call, I learned to understand Lot's desire not to go far. My request wasn't granted, though, and I ended up on the coast of Florida. The weather certainly made the leaving a little bit better. After that move and again after my move to Boiling Springs, I quickly understood Lot's wife. I still look back and wonder what could have been had I gone to college in Maine or if I became a lobster-fisherman like my dad.

In a sense, part of my story is the story of Lot and his wife. Because of my experience, I can understand some reluctance when asked to leave, some not wanting to go so far away, some looking back. I'm sure some of you can relate to Lot's family similarly, or perhaps in a different way if you moved around a lot as a child.

But even if you've never gone far from home, you can still relate to Lot's family. You could be like my dad, who has always lived in Friendship, ME--over 50 years in the same small town. God doesn't ask all of us to leave home in the same way, but eventually we are asked to leave. Eventually, we become different than we used to be, leaving a metaphorical home. For my dad, he turned from a life of anger and alcohol--a life he learned in part from his father and the town that reared him--he turned from that life to the Christ he saw and loved in my mother.

Lot's story is my dad's story. It is my story. It is your story. It is our story. We are all asked to leave home somehow. To be recreated. Reborn. Made new.

No turning back.

All things considered, I think Lot's wife made a better decision than Lot. Lot apparently didn't look back. Lot said he wanted to go little Zoar, because he was old and Zoar was close and small. I figure he wanted to go to a small place for reasons other than proximity. I bet he figured it wouldn't have the problems big cities like Sodom and Gomorah would have. Small towns don't have any problems, right?

In a small town, Lot would have a great opportunity to be the same person he was in Sodom, just in a different place. A new setting doesn't mean a new person. A new setting doesn't guarantee a new beginning. Lot's new groove could soon turn into the same ol' groove. Lot would take new wine and put it into an old wineskin. He would attempt rebirth the way Nicodemus understood it: by climbing back into his mother's womb.

Given the choice between Lot and Lot's unfortunately anonymous wife, I'll choose the pillar of salt. We can read Lot's wife in light of other stories, stories of rebirth and stories that ask us to be the salt of the earth. Let's learn from Lot's wife not to look back, but, friends, to believe the Good News: in Jesus Christ we are forgiven. She looked back and her old self died. Her newness became salt. And when our old selves die we are resurrected. We continue as the salt of the earth--born again to preserve this life in the face of death and adversity, to preserve this life for all, to become God's tools for assuaging the groaning of this earth and for making all things new--to witness and be involved in the transformation from this life to the next.

Making All Things New

Now we can start weaving the tales of our past with stories of our future possibilities--where oldness meets newness in the present.

In Revelation, we read: "Behold, I am making all things new" (21:5). That proclamation is a persistent prophecy. It is true even after it has been fulfilled. God isn't going to make everything new and then stop. So, after you've been born again, you are still a part of all things and, hence, you will be made new again.

And again.

And again.

After we receive this newness, after being "recreated," being born again--whatever you want to call it--it will happen again. We can't rightly flee damnation by living in Zoar. Our newness does not mesh with our oldness. We can't put the new wine into the old wineskin. We can't get find a way back in the womb.

We can't orchestrate our own new beginnings, because we can only comprehend our beginning at birth. God understands infinite regression, and can continually give us new beginnings. And God does just that: makes us new again-and-again-and-again.

Since this is true for all of us, we learn something great from our corporate origin. It is a truth I love to express in the words of a fabulous group of four young men: "I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together." Similar to the mysterious unity of the trinity, we are all one (cf. John 17:22-23)--whether we like it or not. And friends, believe you me, we do not like to recognize our unity, because it means we are Nazis and Jews, the doers and receivers of genocide, the rich and poor, the prostitute, the drug dealer, the homosexual, the straight, the raped child who hasn't eaten for weeks, and the pedophile grown fat from meat and wine. We are the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the naked, the sick, and the imprisoned. And we are also the people who refuse food, drink, friendship, clothes, comfort, and support to those who need it (cf. Matthew 25). And with this knowledge, we discover that as long as one human suffers, we all suffer. We share pain, whether we completely feel and realize it or not.

Fortunately, we have Yahweh who works with us to eliminate this suffering by making new things around us and in us. We all become new in different ways and to different degrees. Sometimes God works little things in us and sometimes we are made completely and utterly new.

In becoming new, we leave our idols and never turn back to them. We put everything on the altar: mother, father, brother, sister, child, cousin, job, spouse, safety, romance, friendship, church, ministry, home, comfort--everything. If any go to follow Jesus, but they don't hate their father and mother, and they don't hate their spouse and children, and they don't hate their brothers and sisters, and they don't hate providing for their children, and they don't hate taking the kids to soccer practice, and they don't hate Sunday-morning services and Wednesday-night suppers, and, yea, they don't hate their own lives, then they can neither be a disciple of Christ, nor a child of God (cf. Luke 14:26).

Sometimes we only need a willingness. Other times the knife must down (cf. Genesis 22)

I recommend really thinking about this sort of sacrificial newness. Seriously. We all might benefit from sitting down to talk with just God, or perhaps God and a small, intimate community. Maybe in your Sunday school class. Maybe with your family. Maybe with your family and another family. Maybe over coffee with a close friend or two. I bet we could all use some deep, creative reflection that immediately actualizes itself in action. And as we reflect and act, God will make us new, so new that we will barely recognize our past self when we look back, die to self, and turn into a pillar of salt for the earth. Just think, in a few weeks, we'll have to start re-introducing ourselves to people in church, because we'll be unrecognizable and really, really salty.

Ah, but newness is painful, because it includes death. So friends, believe the bad news: in Jesus Christ, life won't be easy. But compared to staying the same, the new yoke of Christ is easy. The burden of death and rebirth is lighter than the burden of life in spite of death. It is better for the grave, water, and the spirit to be the womb for your new birth, because the other option is, well ... you know.

Weaving Tales of the Past with Stories of the Future

Sometimes we camp out in little towns after we are made new. Maybe we camp there because we can't handle the newness and we pretend to start afresh. Maybe we camp there because we want the comfort and protection of the womb. Maybe we camp there not because we aren't looking back, but because we never actually looked fully forward, like Lot. We take our newness, but hide it in old wineskins

And sometimes we look back. Maybe we look back longingly, like when I think about Maine. This sort of looking back is understandable, but it has never been beneficial for me.

And when we're near our best, maybe we look back because what we were somehow influences what we are and what we will become. At some point, we must look back to accept our past, learn from it, and share the story. We have holy roots in the past and we cannot sacrifice them, however painful they might be.

Benediction

Today, friends, Easter is behind us and we remember being crucified and resurrected with Christ. Let us now look forward to Pentecost, ready for tongues of fire to descend upon us. Ready to leave here filled with the Spirit and made new.

Again-and-again-and-again.